The Influence Of Demonstrative Evidence In The Courtroom: The District Court Case For Desegregating Schools | BRADLEY V. MILLIKEN

By Lauren Belus

Visual Evidence In the Courtroom

Demonstrative evidence has been used in trials well before modern technology enabled attorneys to use PowerPoints, animations, and trial presentation software. Previously, demonstratives were typically physical items such as a murder weapon in a homicide case or a widely read pamphlet or newspaper to show proof of seditious libel. For the 1971 case of Bradley v. Milliken, involving the desegregation of schools, an interactive map was one of the first uses of a demonstrative in the courtroom. This is an early example of the effective use of demonstratives to persuade the trier-of-fact. Using this historically significant case as a reference, we can clearly see the power of a visual to influence the Court’s decisions and impact the outcome of a seminal case.

A Brief Historical Overview

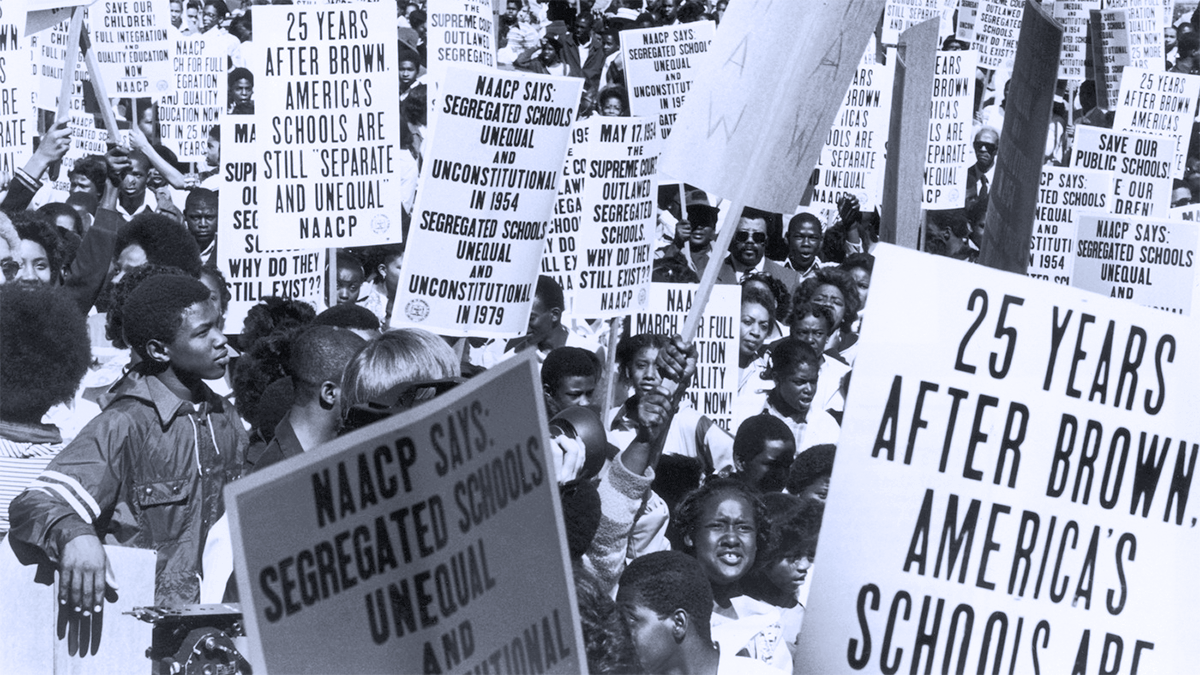

Bradley v. Milliken was a case regarding the desegregation of public school busing across Detroit’s district lines in 1971. This case followed the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which dealt with the integration of public schools across the United States. Although the purpose of Brown v. Board of Education was to desegregate public schools, broader systemic issues, such as the “white flight” of the 1950s and 1960s, as well as widespread redlining of districts, thwarted much of Brown’s intended impact.

By the 1970s, the majority of inner-city schools were predominately black and suburban schools were majority white. This major shift in racial geography can been directly linked to the second “great migration” of non-white Americans and the “white flight” response to this migration in metropolitan areas across the country.

In the 1970s, Detroit, Michigan was one of the most segregated cities in the United States. More than two-thirds of the city’s public schools were black, while the surrounding schools in suburban areas were predominately white.

As the neighborhoods in Detroit became more and more segregated, so did the schools, and the gap in the quality of education grew in parallel. This disparity was evidenced by great differences in funding, supplies, physical conditions of the schools, and quality of the educators and staff between school districts. Schools with predominately black children were barely, if at all, meeting safety codes. Teachers in these school districts would often encourage students not to seek a college education but focus on vocational schools/apprenticeships.

Parents of black students, community allies aiming to end the disparity, and the Detroit branch of the NAACP, organized and created a plan (April 7 Plan) to desegregate 11 of the 22 schools in Detroit. The school board eventually passed the plan, but the state legislature rejected it. At the time, William Milliken, Michigan’s governor, signed this repeal. Plaintiffs then filed a suit against the defendants – Governor Milliken, the Attorney General of Michigan, the Board of Education of the City of Detroit, three members of the Board of Education of the City of Detroit, the State Board of Education, and the Superintendent of the Detroit Public Schools.

The Case

The case was initially petitioned as the plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injuntion to permit the April 7 Plan to be implemented. Judge Stephen Roth presided over this case and ruled that the plaintiffs had presented no evidence that Detroit had a segregated school system and refused to grant a preliminary injunction. However, he required that the Detroit Board of Education develop a plan that would parallel the previous integration levels to be implemented by the next full school year. The plaintiffs appealed to the Circuit Court, which remanded the case back to the District Court on merit of plaintiffs’ substantial claims regarding the segregation of the school system.

The resulting bench trial commenced on April 6th, 1971. The plaintiffs had two primary allegations in this trial:

- The national and statewide housing segregation policies and actions created segregated school systems.

- The actions of the Detroit School Board of Education perpetuated segregated schools.

Visual Evidence | Informing Decisions

Over the course of the 41-day trial, the plaintiffs’ counsel utilized a 10-foot by 20-foot map of Detroit. This map was strategically positioned so that Judge Roth would be able to easily see and reference it at any point during the trial. Unfortunately, there are no pictures of this demonstrative. The following description of the map and its overlays used in court are from the account of Judge Nathaniel Jones, who had served as lead counsel for the plaintiffs.

The map was created by the plaintiffs’ counsel and an urban planner. It showed a simple aerial view of Detroit and had overlays that displayed the shifts in housing trends throughout the city. Each overlay represented five years, starting in 1940 and ending in 1970. Each overlay clearly showed that with each passing decade the geographical positioning of black and white populations shifted, but the housing boundaries remained constant. This geographical shift in demographics was the result of the same trend occurring throughout the United States—the Great Migration (1916 to 1970) and White Flight (starting the 1950s). The map also very clearly showed that the school assignment boundaries matched exactly with these housing boundaries. During this period in the 1970s, activists across the country were arguing that educational disparity among black school children was the direct result of redlining and housing segregation. This point was driven home by the plaintiffs’ use of the color-coded map and overlays providing visual evidence to support their oral arguments and educate the judge.

During the course of the trial, Judge Roth became more skeptical of the defendant’s arguments as he returned repeatedly to this map. In Judge Roth’s notes he states “The Southwestern-Western and Denby-Southeastern optional areas are all white on the 1950, 1960 and 1970 census maps. Both Southwestern and Southeastern, however, had substantial white pupil populations, and the option allowed whites to escape integration. The natural, probable, foreseeable and actual effect of these optional zones was to allow white youngsters to escape identifiably “black” schools.”

Judge Roth ultimately ruled that the Detroit public school system was guilty of de jure segregation due to housing segregation and the specific policies and practices of the school board and state officials. He ordered a metropolitan busing plan to achieve integration in the Detroit public school system.

The Bradley v. Milliken decision joined other court rulings to dismantle school segregation in the early 1970s. A few notable cases are Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education (1971) and Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia (1972). During this time, however, President Richard Nixon continued to voice his stance against school busing as a tool to forcibly desegregate schools. In a 1972 New York Times recording of the President’s address to the nation on the matter, he states, “The reason action is so urgent is because of a number of recent decisions of the lower Federal courts. Those courts have gone too far; in some cases, beyond the requirements laid down by the Supreme Court in ordering massive busing to achieve racial balance.” The Bradley v. Milliken decision was appealed and was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court where Judge Roth’s ruling was overturned. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court found that, in light of “no showing of significant violation by the 53 outlying school districts and no evidence of any interdistrict violation or effect,” the district court’s remedy was “wholly impermissible.” The Court also stated that schools should have local control over their policies.

It is important to note that Judge Roth’s decision was clearly influenced by the Detroit map, effectively used as a demonstrative by the plaintiffs. This map was able to persuasively show the demographic shifts in the city and how those shifts aligned with the housing/school boundaries. This map, along with strong oral arguments, was able to sway an initially skeptical judge to rule in favor of the plaintiffs and find that “The principal causes undeniably have been population movement and housing patterns, but state and local governmental actions, including school board actions, have played a substantial role in promoting segregation.” Regardless of the type of case, the Bradley v. Milliken result demonstrates that the design of demonstratives is a critical aspect of any trial strategy to educate and persuade the trier-of-fact.